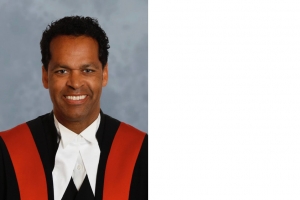

Recognizing the urgent need for more Black lawyers and judges in the legal profession, the Honourable Judge David St. Pierre, the Honourable Justice Selwyn Romilly, Vancouver lawyer Matthew Nathanson, and two anonymous donors established Allard Law's first-ever award to support incoming Black JD students in June 2021.

Judge David St. Pierre put himself through school, in part, by playing guitar in a band. When he was about 18, he was arrested for allegedly being in possession of a “prohibited weapon”: St. Pierre had just come off the stage at a big show and was wearing a studded wristband.

“I cannot understate how humiliated and embarrassed I was at the time. I could not understand how I, a young university student who had never been in trouble with the law, was now in danger of having my whole future ruined. Thankfully, the very capable young defence lawyer, who I was forced to hire, persuaded the Crown to view the wristband,” shared St. Pierre.

It was then determined—of course—that a studded wristband was not a prohibited weapon and the charges were eventually dismissed. However, the event made clear to St. Pierre the immensity of the power of the state to interfere with one’s liberties, and beyond that, the fact that it was his lawyer who was essentially the only one checking those powers. “I thought that if I could do that work someday, it would be very important work.”

St. Pierre attended the University of Alberta to get his undergraduate degree in psychology, but then took some time off before going to law school. In that time, he worked as a musician, and music still plays a significant role in his life: “As Prince might say, love is too weak to define just what music means to me. I still play in a few bands. It is my therapy and the way I free my mind. It is the great uniter. When I am playing music I, literally, cannot have any other thoughts invading my brain. I would say that it has enabled me to be a better judge because I have an outlet where frustration and stress can be safely released.”

So, after a few years as a professional musician, St. Pierre attended the University of Calgary Law School. “I loved my time [there]. I had very enthusiastic and talented professors and always felt welcome and respected.” While at law school, St. Pierre participated in the students’ legal advice program, helped to found the Black Law Students’ Association of Canada, and was part of a task force that was drafting human rights legislation in Alberta. After getting his law degree, St. Pierre practiced criminal law in Vancouver.

“I have always been interested in the application of the Charter in the criminal law context. […] As a Black man growing up in North America you are acutely aware of the impact of race in all institutions in society, especially the criminal justice system. The Charter of Rights and Freedoms says that every individual is equal before and under the law. Of course, this is not always true. I love the ideal that the Charter promises. My goal is to help make that promise a reality in all the work that I do.”

In 2009, St. Pierre stepped into the role of judge, welcoming the great challenge of being an impartial adjudicator after being an advocate for 15 years. St. Pierre had always admired the judiciary and the ability of judges to weigh and balance a whole host of different and important societal factors before deciding a case: “Legislators change the laws from time-to-time to adapt to a changing world. Judges, commensurately, must interpret those laws to ensure constitutional compliance. It is a fascinating interplay and one that often leads to a re-examination of whether old beliefs need to be adapted to the changing times.”

St. Pierre is attentive to changing times outside of the court room, as well. “I grew up in a family with very modest financial resources. I had to pay for my own education from the time I left high school. When I attended law school, what seems like a very long time ago, I held down several jobs in order to pay the bills. Today, the costs of going to law school have skyrocketed. I struggled then and the costs now are exponentially higher than when I went.”

To that end, St. Pierre, Justice Selwyn Romilly, Matthew Nathanson, and two anonymous donors established the St. Pierre, Romilly, Nathanson Entrance Award in Law for Black Students. “We just thought that there are many disadvantaged students out there who are intelligent enough, motivated enough, and capable enough to do well at law school but are being held back by financial barriers. We thought it was time to do something about that. Without going into detail, the statistics are clear. The data establishes a substantial gap in the wealth difference between Black Canadians and the larger population. Finances should never be a barrier to entering the profession.”

St. Pierre shared that the three named donors have not just committed financial resources to this endeavour, with mentorship and other kinds of supportive relationships being so critical to the growth and development of the legal community: “We are also making a commitment to mentor and support these students on their path to the bar, or some other vocation that involves the law.”

As to his own mentors, St. Pierre named Judge Romilly himself, who was a judge for some 40 years. St. Pierre met him while in law school, and Judge Romilly has been an amazing mentor ever since. Romilly was the first Black judge appointed in BC. When asked about progress made in the law on issues of racism and diversity, St. Pierre remarked that—depending on who you ask—there might be disagreement on whether or not progress has actually been made, given that there were many years before Romilly was joined in his position by another Black judge.

“That said, there is reason to be hopeful. All institutions in society are waking up and recognizing the obvious benefit there is in celebrating diversity. The legitimacy of our institutions is more easily achieved if those places look representative of the whole community, not just certain segments. I would like to see the opportunity to achieve merit receive some attention in our society. A meritocracy, whatever your definition, only works if those in it have an equal chance of gaining merit.”

The St. Pierre, Romilly, Nathanson Entrance Award in Law for Black Students is one first step toward achieving that equal chance of gaining merit, with the hope that it will eliminate financial barriers for many students who may be thinking of coming out west. “The BC legal community is becoming increasingly aware of the value of diversity. Acting on that recognition would be so much easier if there was a talented group of Black law graduates to fight over.”

As additional encouragement for prospective Black students considering studying law, St. Pierre offered this advice: “I would say to Black students considering law to just go for it. There is a belief among many young justice warriors out there that to become a member of, what is thought to be, an historically oppressive colonial system is to support the old ideals and goals of that system. I respect the argument. However, in order to effect change within an institution I believe that you need both outside and inside pressure. The presence of progressive minds inside an institution is critical for positive change to occur. As far as feeling out of place? You are not alone. There may be very few people around you with shared experiences however there are great number of thoughtful and motivated allies…that will join you in your quest for a more inclusive space.”

First published on February 23, 2022.